Contact us

401 W. Kennedy Blvd.

Tampa, FL 33606-13490

(813) 253-3333

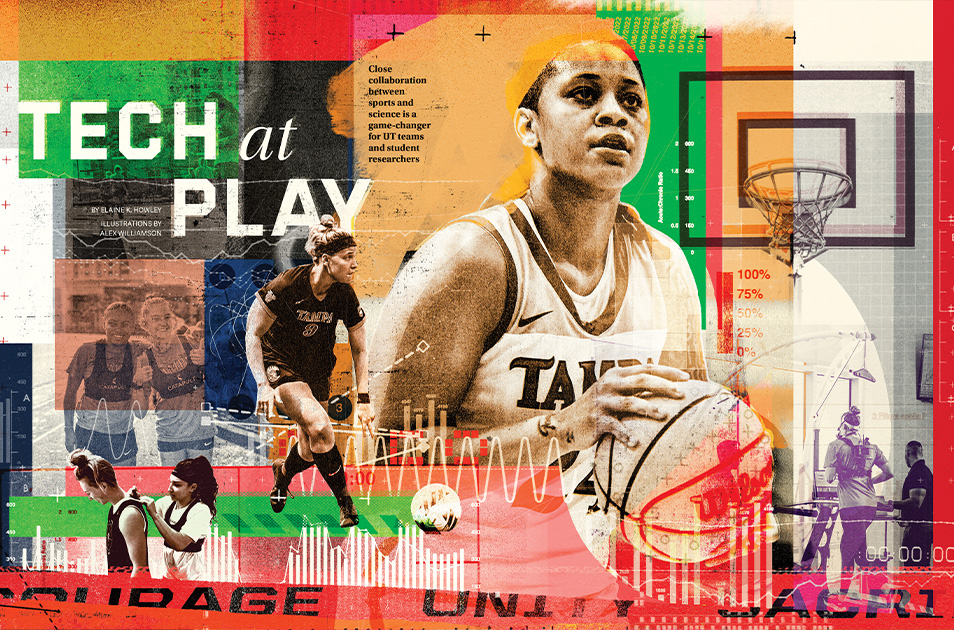

Close collaboration between sports and science is a game-changer for UT teams and student researchers

More UT News