Contact us

401 W. Kennedy Blvd.

Tampa, FL 33606-13490

(813) 253-3333

A 3.4 million-year-old fossil solved an anthropological mystery that lasted over a decade.

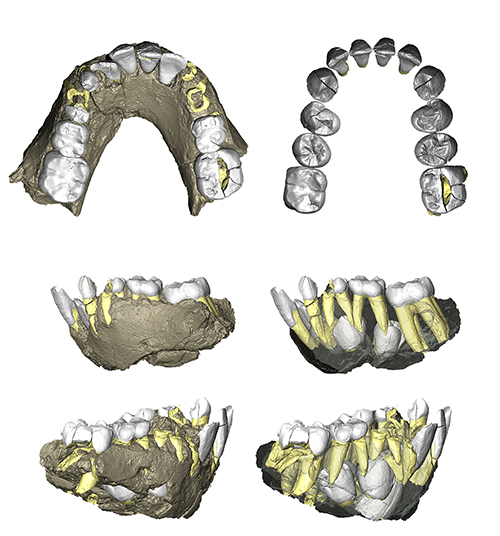

Replica of mandibles assigned to Australopithecus deyiremeda. Photo by Steve Filmer.

A prehistoric jawbone studied by Anna Ragni, assistant professor of biology, could give insight into both the past and future of humankind.

The nearly complete juvenile mandible belonged to a species of human ancestor and was found in Ethiopia in 2016, then brought to Ragni in early 2023 when she was a postdoctoral researcher at Arizona State University, immediately before she started at UTampa. The jawbone was determined to be from the same species as a mysterious foot fossil found in the same location in 2009 by Ragni’s colleague at ASU, which had gone unidentified since its discovery. Once there was a body part above the neck that was clearly associated with the foot, the species was identified as Australopithecus deyiremeda.

A paper recently published in the research journal Nature, co-authored by Ragni, reached two major conclusions based on the species identification. This discovery meant that multiple types of human ancestors existed at the same time in the same place, and that bipedality — walking on two legs — came in different forms.

That’s because the bones of the mystery foot had a different shape than other known human ancestors from the same region and time period, such as the famous “Lucy” species, Australopithecus afarensis. A. deyiremeda had long, curved toes and a big toe that stuck out to the side like a thumb, while Lucy’s toes were in line, like a human. While both could walk upright on two legs, the flexible toes and opposable big toe of the mystery foot were designed for climbing and living in trees, while their relatives were on the ground right below them. “Were they unknowingly passing each other like ships in the night, or did they see each other and were just like, ‘Hey’?” pondered Ragni.

Ragni got involved with the anthropological breakthrough due to two of her past research experiences: studying teeth and digitally analyzing anatomical models. While working on her master’s, she looked at fossils of human ancestors that were more than a million years old to figure out what they were eating. Then, for her doctoral dissertation, she developed her skills in digital analysis of internal bone structure.

Because the jawbone belonged to a child, many of the permanent teeth were still inside of the bone. “When you have a one-of-a-kind priceless fossil, you want to look inside at those adult teeth that still haven’t come out yet,” said Ragni. However, “you can’t just take a hammer and break it.”

Instead of chiseling away on the 3.4 million-year-old artifact, Ragni digitally pulled it apart using micro-CT scanning technology, segmenting every adult tooth and individually extracting each one. After thorough analysis, Ragni and her colleagues determined the specimen’s age (4.5 years old) and diet (forest vegetation)

While Ragni’s work on the project is complete, she said that researchers can use the fact that Lucy and A. deyiremeda persisted during a time of climatic change to better understand changes in climate today. “Much of this research is relevant because we’re living through climatic change right now,” she said. “How did that impact the population levels of these ancient relatives of ours? How did that impact the foods that were accessible? Those are the types of questions that my entire field is trying to answer.”

At left, 3D renderings of the juvenile mandible. The teeth on the right side are the permanent teeth. Rendering by Anna Ragni

Funding for this project was provided by the National Science Foundation and the W.M. Keck Foundation. Field and Laboratory research in Ethiopia was facilitated by the Ethiopian Heritage Authority.

More UT News