Published: December 09, 2020

In a Class of Her Own

High school math teacher Ashley Kearney ’12, who is improving outcomes for students in her hometown of Washington, D.C., won the nation’s highest honor for STEM education.

By Jane Bianchi

Photograph by Chris Hartlove

At the beginning of each algebra and calculus class, Ashley Kearney ’12 doesn’t dive right into numbers. First, she looks at the faces of her 18 students (since the pandemic, through a computer screen) and runs a “mood meeting.” Everyone talks about how they’re doing and what’s motivating them.

“Students bring a lot to class with them,” says Kearney, who teaches at Ron Brown College Preparatory High School, an all-male public school that serves about 261 students in Ward 7 of Washington, D.C. — near Ward 8, where she went to elementary school.

She doesn’t just teach math; she stresses the importance of attendance and pushes students to see themselves as capable. “If you come in with assumptions that the students can’t perform, then you start teaching them like they can’t,” says Kearney, who is constantly asking: How can I raise the rigor of the content?

Another goal is teaching them power structures. When students complain, she challenges them to ask: Is this a city council issue? A school board issue? “I want them to use their voices and understand that they’re in charge of their educational experience. They don’t have to just accept problems,” she says.

And she leads by example. Frustrated by the school’s lack of an A.P. calculus course, Kearney — who spends many evenings at community meetings with a group that she helped form, D.C. Education Coalition for Change — figured out how to add one.

One person who has always been impressed by her perseverance and dedication is Benjamin Williams, the former principal of her school who worked with her for three years. “I’ve never been around an educator who lives in her purpose the way that Ms. Kearney does. She truly believes that every young person that walks into her space can achieve,” he says.

Kearney’s extra efforts were recognized this past year. In February, she was chosen as the 2020 Teacher of the Year by D.C. Public Schools, and in August, she was one of 107 U.S. educators who won the Presidential Award for Excellence in Math and Science Teaching, the country’s highest honor for teaching those subjects (grades seven through 12). The latter award has been administered by the National Science Foundation on behalf of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy every year since 1983.

“I’ve never been around an educator who lives in her purpose the way that Ms. Kearney does. She truly believes that every young person who walks into her space can achieve.” — Benjamin Williams, the former principal of Kearney’s school.

Finding Her Path

Kearney knows Washington, D.C., well because it’s where she spent most of her early childhood. Just before middle school, her family moved to rural Georgia, where her grandparents owned land and were involved with a local African Methodist Episcopal church. “We would do a lot of programming for the community — anything that related to uplifting people, particularly people of color,” she says.

The second-oldest of five siblings, Kearney developed discipline in high school, while her parents were often assigned 12-hour night shifts as factory workers. She kept busy as the point guard of her basketball team, was elected class president all four years, worked as a part-time bookkeeper at a local grocery store and volunteered for her city’s first Black mayor.

She found herself enjoying and excelling in math classes, even when she was sometimes the only Black person and the only woman in the class. “There were English classes that I had taken. When I would write papers and try to explain things from my perspective, sometimes they were graded very subjectively or the teacher didn’t see the value of the thought. Math was the one place where it was very much like this universal language that you can’t really say is wrong. You can debate the process, but you can’t debate the answer,” she says.

Kearney had initially dreamed of becoming a sports agent, and UT’s sport management program appealed to her. She found her best friends on campus as president of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority. “To be surrounded by people who look like you, are just as educated, just as motivated and then pull you up, give you all the information that you need, support you and teach you how to be a woman — it was transformational,” she says.

Another transformational moment occurred when taking a job at Academy Prep Center of Tampa, a nonprofit middle school in Ybor City that serves students qualifying for need-based scholarships. She started tutoring math students and loved it so much that she skipped going home to Georgia so she could keep working there every summer.

Though she won an award from the Department of Sport Management and was offered a job in the industry in Naples, FL, before graduating from UT, her heart was no longer in it. Once her supervisor in the Office of Student Leadership and Engagement, Megan Frisque, showed her a brochure for Teach for America — a nonprofit that places teachers in low-income schools in places like D.C. — her path was clear.

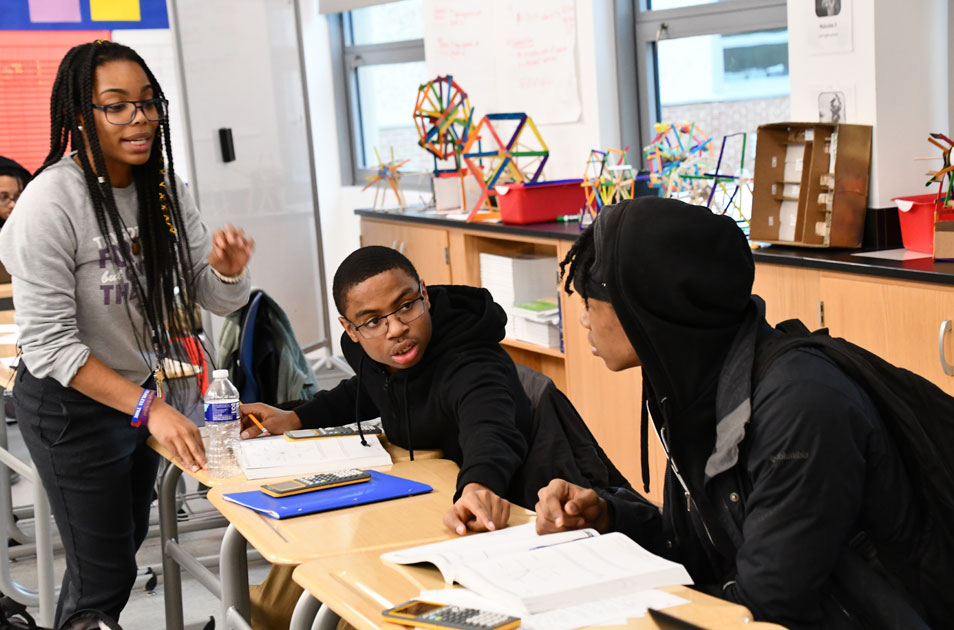

Ashley Kearney ’12, left, teaching an algebra class in February 2020 at Ron Brown College Preparatory High School. Photograph by Anthony Tilghman

Putting in the Work

Kearney has been teaching math in D.C. for eight years (the first two were with Teach for America). She spent one year at Ron Brown Middle School, four years at Anacostia High School and is now in her fourth year at Ron Brown College Preparatory High School, a high school that’s named after the first Black U.S. commerce secretary.

She’s dealt with many challenges along the way, including high turnover, especially among principals. “It was hard to deal with because you would build all these relationships and you would have these initiatives and then someone would come in and have their own initiatives and you’d have to switch gears — and also try to hold onto the progress you’d made,” she says.

But she’s watched with joy over the years as her enthusiasm for advocacy has spread at her schools. For example, one student government group decided to raise money to hire an artist to give a presentation to boost mental health and collaborate with alumni for a homecoming parade.

And it’s not just students who benefit from her encouragement and commitment. Kearney, who got her master’s in curriculum and instruction from Johns Hopkins University at night, has devoted a lot of time to coaching her fellow teachers, sharing helpful resources with them and furthering their professional development to raise the level of teaching throughout each school.

Though virtual instruction is particularly “exhausting” — especially when teaching young men with high energy who love horseplay — it’s also fun. She finds inspiration through her students, who gave her a standing ovation and screamed her name during a pre-pandemic assembly when her Teacher of the Year award was announced. A couple of them have already told her that they want to become math teachers someday, and some recent graduates message her on Instagram: “My college math class is too easy!”

What else drives Kearney: her idols, like Mary McLeod Bethune, a child of former slaves who opened her own school and became a world-renowned educator and civil rights leader. “It all comes from wanting people to have access. The one thing I can give back that I’m also good at, where I know I can make a difference, is math. A lot of times people grow up saying, ‘I’m not a math person,’ and we get to change that. And by changing that, you’re changing so many other options — that person might decide to go into engineering,” she says.

After boosting her own trajectory, Kearney is now helping hundreds of young people reach new heights. Perhaps someday she’ll become an administrator — but only if she can keep teaching part-time.

One thing is clear: Whatever she does will add up to excellence.